A fascinating story in Mother Jones explains how one tech startup is working to end animal suffering, one gene at a time — and how government regulations and anti-GMO crusaders might stop him.

When Scott Fahrenkrug, founder of the startup Recombinetics, saw what happens when dairy cows are dehorned — a horrifically painful process that involves burning or cutting away tissue before it turns into horns — he wanted to help.

“I started talking to producers, and it became real clear to me that it wasn’t just me being touchy-feely,” he says. Dairy farmers told him they hated dehorning calves, and they were under pressure from animal welfare groups and customers, like General Mills and Nestlé, to phase it out.

Fahrenkrug knew that some breeds of cattle naturally don’t grow horns; the problem is that these “polled” cows traditionally have been lousy milk producers.

But in 2012, animal geneticists identified a bit of bovine DNA that controls hornlessness. Fahrenkrug, who specializes in a newly developed genetic modification technique known as precision gene editing, realized it would be a snap to rewrite the corresponding DNA in an embryo of a dairy breed.

Presto: Hornless cows that give a lot of milk.

Suddenly, a lot of the necessary evils around meat and dairy farming don’t seem so necessary anymore. Fahrenkrug sees this kind of application for gene editing everywhere.

Fahrenkrug thinks hornless milk cows are just the start. Recombinetics is tweaking the DNA of a few high-performance cattle breeds so they are more heat tolerant and can thrive in a warming world.

He has developed piglets that are resistant to common diseases, and has plans for meatier goats to feed a growing global population. Fahrenkrug’s ultimate goal is animals with just the right mix of traits — and much less suffering.

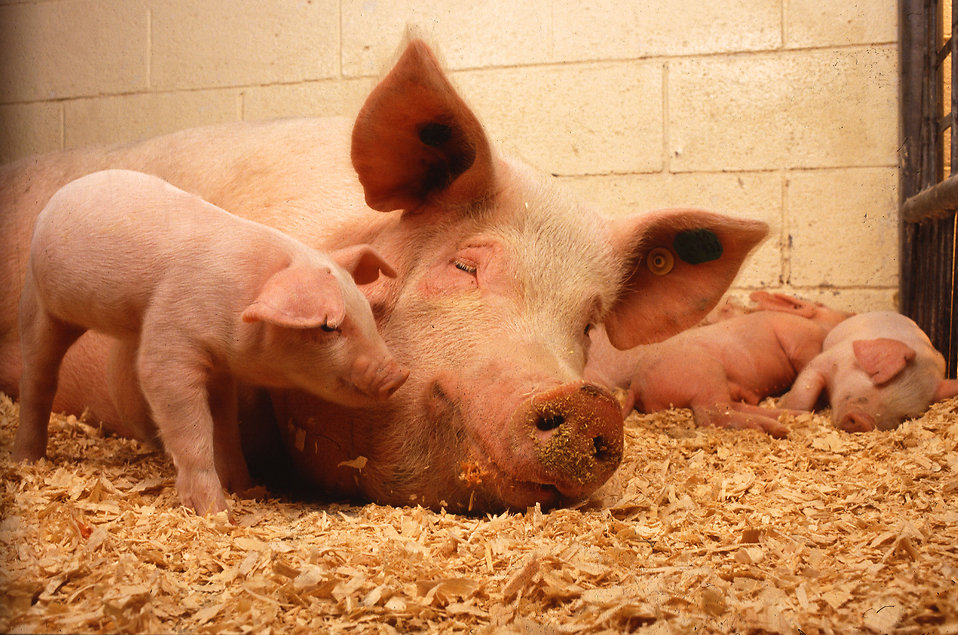

One particularly unpleasant (and previously unavoidable) bit of pig farming is castrating male piglets:

Because the meat of sexually mature male pigs can develop a funky locker-room smell called boar taint, male piglets raised for pork routinely have their testicles removed to prevent puberty. Like dehorning, it’s a painful procedure that costs farmers money. …

In another Recombinetics barn in Wisconsin live a different group of male pigs that are missing a gene called KISSR, which controls sexual development hormones. As they grow up, their testicles will never enlarge and descend and they will never develop that unmistakable ripe smell of an adult boar.

As commercial animals, they would save farmers the cost of castration, and they would maintain the superior “feed conversion rate” of prepubertal animals — meaning that they get fatter more quickly on less food. …

Fahrenkrug calculates that the $23.4 billion US pig farming business could stand to gain $1 billion by switching to pigs that don’t need to be castrated.

Of course, nothing in this world is simple. The technology itself is safe, straightforward, and well-understood, but like all progress, there’s nothing so cool and so beneficial that the government can’t screw it up.

The government has never approved a genetically engineered animal, and for small companies, the regulations and hurdles for GMO foods are nearly insurmountable.

Even for plant crops, it can take a decade or more (and $136 million) to discover, develop, and get approval for one new variety. About half of that time is spent navigating the regulatory thicket of USDA, FDA, EPA, and 70 other international agencies that regulate GMOs.

And no variety of biotech animal has ever made it through the process:

Many GM crops are now on the market, yet no GM meat animal has ever made it that far. Scientists at the University of Guelph in Ontario at one point created the Enviropig, a transgenic hog with a mouse gene that produced less water-fouling phosphate in its manure. That project ran out of funding and backers while awaiting regulatory approval, and the last Enviropigs were slaughtered in 2012.

A fast-growing transgenic salmon, which has a gene from another fish called an ocean pout, has been in the regulatory process in one form or another for 20 years, and it is not popular. A preliminary FDA assessment in 2012 attracted 38,000 public comments, mostly of the “vehemently opposed” variety.

Fahrenkrug is optimistic about the chances for his hornless cow: because the trait is already found in cows, he argues that the FDA has no authority to regulate something that cattle breeders do all the time with no regulation at all.

But the FDA doesn’t agree, simply asserting that it has the power to regulate or prohibit any engineered animal, even if the exact same trait is found in nature and even if it could be acquired through ordinary breeding.

There’s no good reason for this regulation, but throwing hurdles in front of new technology and progress is what the government does.