Do prediction markets have any idea what’s going on these days? They persistently and wildly underestimated both Trump and Brexit. If betting markets can get the two most well-studied, well-polled, and consequential political events in recent history dead wrong, how valuable are they really?

Of course, nobody ever said prediction markets were perfect, but many people (myself included) have repeated the conventional elite wisdom that betting markets are better predictors than polls. But in these cases, they were not only no better than polls, they were much, much worse.

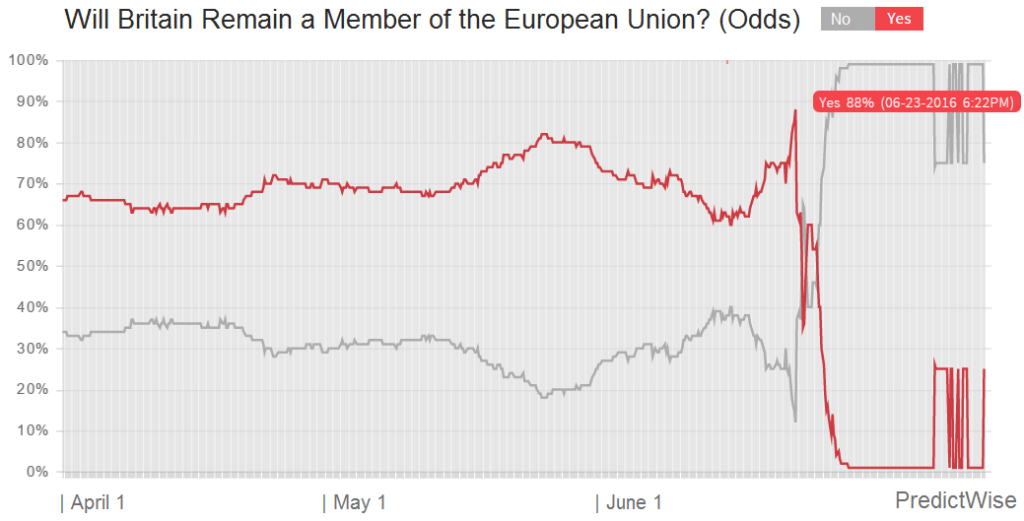

No reasonable look at the hundreds of polls on Brexit would have suggested that there was a 90 percent chance of Britain remaining in the EU, but that’s where the bettors put the odds on the day of the vote.

Even worse, Trump crushed the horse race polls in most states and nationally for virtually the entire time he was in the primary race.

But bettors didn’t put Trump’s odds of winning the primary above 25 percent until just a couple weeks before Iowa — and then when Trump lost Iowa by a small margin to Ted Cruz, the market wildly overreacted: Trump’s odds cratered from 50 percent to 20 percent. Marco Rubio (who came in third!) was catapulted to over 50 percent.

All because of results in Iowa, which is known to be not terribly predictive. Past GOP winners: Mike Huckabee (2008), Rick Santorum (2012), and Ted Cruz (2016). (In 1996 and 2000, fringe candidates Pat Buchanan and Steve Forbes also came in strong second places there, with 23 percent and 31 percent of the vote, respectively.)

Rubio’s odds plummeted after being crushed in New Hampshire, but then steadily crawled back, until being crushed again, because of a huge loss in the tiny Nevada caucuses.

It wasn’t until after Trump started racking up serial victories that the odds swung consistently in his favor. Even then, it’s hard to say that the markets were pricing the odds correctly, with Kasich at 10 percent and Cruz at 25 percent into April. In any case, if the markets can only get it right after the elections absolutely refute them, they aren’t really that useful. Any idiot can see Trump is winning after he’s won New Hampshire, South Carolina, Nevada, and most Super Tuesday states.

Similarly, the odds against Brexit hit 88 percent the night of the vote, and it wasn’t until unexpectedly bad results for Remain started pouring in from across the country that they flipped.

So why? Why are the polls out-performing the markets?

In the case of Trump, the odds suspiciously track elite opinion. (By “elites,” I mean highly educated, upper-middle class, and politically literate types, well represented by journalists and pundits.)

Trump was written off as a joke by commentators and “data journalists” for 7-8 months before the primaries. Then, as Iowa loomed closer and his long-predicted collapse failed to emerge, elites began to get nervous and take him seriously. Then Trump failed to win Iowa, and Rubio did better than expected, and since Cruz was still written off as unelectable, political commentators settled on a new establishment front runner in Rubio.* But Rubio got creamed in race after race, and Trump racked up victory after victory.

Elite opinion (at least, in my just-so, hindsight observation) and the markets tracked each other very well. What elite opinion and the markets didn’t track well were the polls, which showed Trump with large, sustained, and durable leads among GOP voters. My guess is that the types of people who know about and participate in betting markets are elites, and the conventional, consensus wisdom among elites drives political bettors more than a sober analysis of the data.

But in Britain, the prediction markets are large and highly liquid. It’s not a niche hobby — all classes bet on everything. So whither the wisdom of crowds? I have no idea, and nobody else seems to either.

Here’s why I find this all so concerning:

* Here’s Nate Silver after Iowa claiming to interpret the markets and why 3rd place improved Rubio’s odds so much — and, for good measure, here I am doing the same thing. In reality, our opinion (or the elite consensus it represented) was likely what was driving the market. (This is also, notably, the last time Five Thirty Eight had any article about betting markets.)